In early 2022 the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) completed a

project to update the evidence base on wood dust exposure risks in

British manufacturing industries. In so doing, HSE gained a better

understanding of how it could support small and medium-sized

woodworking enterprises in controlling exposure to wood dust.

Airborne wood dust created during hand-held powered sanding

(© Crown Copyright, Health and Safety Executive)

The Challenge

There is a legal duty on employers to ensure that workplace

exposures do not exceed a given workplace exposure limit (WEL), to

follow good control practices and, for carcinogens and asthmagens,

to reduce exposure to as low a level as is reasonably practicable

(ALARP). Exposure to any wood dust can cause asthma and dermatitis,

whilst exposure to hardwood dust can also cause sino-nasal

cancer. At the time of this research, the WEL in Great

Britain for both softwood and hardwood dust was 5 mg/m³, based on

an 8-hour time weighted average (TWA). The limit for hardwood and

mixed hard and softwood dusts has since been reduced to 3 mg/m³ but

the WEL for softwood dust remains at 5 mg/m³. The Control of

Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) regulations remain

unchanged.

The Solution

Occupational hygiene assessment visits were carried out at

twenty-two woodworking manufacturing sites. The sites were selected

on the basis that they were believed to be following reasonably

good occupational hygiene control practice, enabling good practices

to be benchmarked. The sites visited covered furniture production,

joinery, saw milling and boat building. The sites were also invited

to participate in telephone interviews to gain a better

understanding of how HSE could support small and medium-sized

woodworking manufacturing enterprises in managing the control of

exposure to wood dust.

The Outcome

Overall 252 8-hour TWA wood dust exposure measurements were

obtained, of which 6% were greater than 5 mg/m³. Ten of the

twenty-two sites had at least one exposure greater than 5 mg/m³.

Out of the 216 exposures for sites which produced hardwood dust,

18% exceeded 3 mg/m³, the new WEL for hardwood (and mixed wood)

dusts.

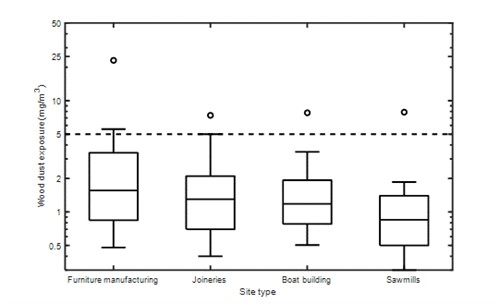

Figure 1 Wood dust exposure measurements by site type (8-hr

TWA)

The data are presented in a boxplot (Figure 1), where the circle

represents the highest exposure in that dataset, whiskers represent

the 10th and 90th percentiles, and the box represents the median

and 25th and 75th percentiles of the data. The dashed line

represents the WEL for hardwood and softwood dusts current at the

time of the survey. The sites were selected as good health and

safety performers, but exposures greater than the WEL were found in

all four sectors.

A number of task-based exposure measurements were also made for

cleaning and maintenance activities. Exposures for 3 out of 10

workers who were dry sweeping, and 5 out of 11 workers who were

changing waste sacks on dust extraction air cleaners, exceeded a

nominal 15 mg/m³ 15-minute short-term exposure limit (STEL). There

is no legal STEL for wood dust exposure, but a figure of three

times the long-term limit is recommended as a guideline for

controlling short-term peaks in exposure (EH40/2005 Workplace

exposure limits). For respiratory sensitisers such as wood dust,

activities giving rise to short duration peak concentrations are of

particular concern. Performing these short duration, high exposure

tasks made a disproportionately large contribution to the workers'

8-hour TWA exposures, significantly adding to their health

risk.

Dry sweeping is bad practice because it generates

high levels of airborne dust and should be

avoided.

Local exhaust ventilation (LEV) provision for fixed woodworking

machines was generally adequate to control wood dust exposures to

below 5 mg/m³, but was found to be poor for hand-held power tools

(e.g. orbital sanders and routers) and manual sanding. Most fixed

LEV systems underwent a 14-monthly thorough examination and test

(TExT), but most portable vacuum systems did not.

The management, selection and use of respiratory protective

equipment (RPE) was poor; the main issues were selection of

RPE with too low a standard of protection, lack of face fit testing

for tight-fitting RPE, and the incorrect use of RPE (e.g. use of

tight-fitting RPE with facial hair). Seventy-eight workers wore RPE

at some point, but only twenty-five were face fit tested and wore

it correctly.

Eight of the twenty-two sites had commissioned their own dust

monitoring survey and, although there was a reasonable likelihood

of health effects occurring in these sectors, only thirteen of the

sites had health surveillance in place.

Employers obtained information on how to control wood dust from

various sources. The most commonly mentioned source was the HSE website. They

recognised the health risks associated with exposure to wood dust

as well as the benefits of controlling wood dust, including

protecting workers' health, less time spent cleaning the workplace

and improved productivity. They also acknowledged a positive impact

on product quality. Approaches needed to raise awareness and

promote good practices among the workforce included challenging

poor practices and leading by example, as well as providing

information on the health effects of wood dust exposure and the

importance of controls. Challenges included worker attitudes toward

controls, poor habitual working practices, and limited availability

of resources for smaller companies.

In summary

- Many sites did not adequately control worker exposure to wood

dust. Employers are recommended to review their exposure

controls and implement any necessary improvements to comply with

the new WEL and meet the requirements set out in the COSHH

Regulations.

- Sanding was the activity that led to the highest long-term

exposures, whilst cleaning and maintenance tasks gave rise to high

short-term peak exposures which resulted in a disproportionate

effect on overall wood dust exposure. It is recommended that these

activities receive particular attention when managing the risks

from airborne wood dust.

- LEV performance was taken for granted on many sites and

daily/weekly maintenance checks were not carried out. Regular and

effective use of LEV with hand-held power tools was not observed.

Employers should ensure suitable LEV is both provided and used

effectively for fixed woodworking machines and for hand-held power

tools. LEV should be regularly checked and maintained for effective

performance and subjected to a TExT at least every 14 months.

- There was often a lack of knowledge about the management,

selection and use of RPE, and little training or supervision of

workers wearing RPE. Employers should ensure that the RPE chosen

offers adequate protection for the task, and is suitable for the

worker (e.g. face fitting is properly carried out for tight-fitting

RPE). They should also ensure that the RPE is used and maintained

correctly.

- Some sites lacked health surveillance for wood dust exposure.

On woodworking sites, where there is a reasonable likelihood that

workers could develop occupational asthma and/or dermatitis, a

health surveillance programme should be in place. This programme

should be set up by the employer in consultation with a competent

Occupational Health professional.

- Workers' engagement in healthy and safe working practices is

crucial. Employers might benefit from using risk communication

approaches that focus on increasing workers' awareness of their

susceptibility to ill health and encourage the use of controls.

Communication using credible sources, such as peers, may enhance

effective uptake of the message. Benefits relating to the control

of wood dust, such as improved productivity and product quality

could serve as a means of promoting good practice across the

industry.